Between Jazz Bars and Quiet Alleys, Chasing Murakami in Tokyo

- Niranjana H

- Jun 7, 2025

- 4 min read

There’s something wonderfully lonely about walking through Tokyo with Haruki Murakami in your backpack. Not the man, of course (he’s probably out running a marathon), but his books, his obsessions, his cities. Especially if you’re an Indian reader who’s grown up with local trains that rattle, chai that stings, and heat that doesn’t ask for permission. Tokyo, in contrast, hushes. It smooths itself out. And then, just when you think you’ve figured it out, it splits open like a parallel universe.

Retracing Murakami’s Tokyo is not an official map or a government-endorsed trail. There are no plaques that say “ Here, Toru Okada stood and watched the world end slowly”. But the coordinates are there for those who look. jazz bars tucked into basements, curry shops where silence is served hot, parks where cats linger a little too long. And when you, the Indian traveler, find yourself standing there at a seemingly nondescript alley, a bridge, a bookstore, you are gripped by a feeling that the Germans call fernweh, the Japanese call natsukashii, and the internet calls sonder. The realization that everyone has a story.

And that Murakami, somehow, has written parts of yours.

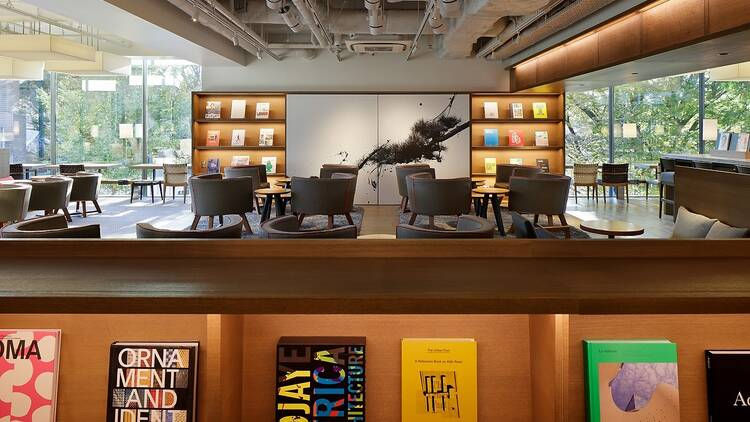

Start with Daikanyama Tsutaya Books. It's not strictly Murakami-land, but it feels like the sort of place where his characters might find themselves without knowing why. Warm wood, ambient jazz, an entire corner dedicated to Murakami’s works in Japanese and translated languages. I saw a young woman leafing through Norwegian Wood while sipping a matcha latte, headphones on, eyes watery. And for a second I wanted to ask her: Midori or Naoko? Who hurt you first?

From there, it’s a train ride to Kichijoji, a leafy neighborhood that feels like the Tokyo version of Bandra on a rainy Tuesday. calm, creative, almost shy. This is where Murakami once lived, and where his novel Norwegian Wood cradles much of its sadness. Inokashira Park, in particular, is where memories pool. Couples rent boats, old men feed birds, and every now and then, someone sits too still, like they’re listening to a sound only they can hear. It’s the kind of place where an Indian reader might sit on a bench and remember an unfinished love story from college, one that still smells like rain and too many WhatsApps left on read.

One of the most surreal stops was Ochanomizu, a sleepy university area with bookstores and guitar shops. This is where 1Q84’s alternate worlds begin to bleed into each other. There’s nothing explicitly magical about the neighborhood, and yet, as I walked past a vending machine that only served milk tea, I had a moment. A crow cawed. A cat blinked at me. I looked up and wondered: Is there a second moon? The Japanese call this “ma” the in-between, the space that exists between time and meaning. Murakami builds entire lives in that space.

And just a few stations away, in Shinjuku, you’ll find Nakamuraya, a legendary curry house that feels like another such portal. Opened in the 1920s, it serves a version of Indian-style curry brought to Japan by Rash Behari Bose, the Indian revolutionary who sought refuge in Tokyo and married into the Nakamuraya family. You sit there, eating a plate of slow-simmered

curry rice, and something happens. Two worlds collide. The rice is Japanese, the masalas unmistakably subcontinental. It’s as if reality hiccups, and for a second, 1Q84’s shadow world slips into view. For an Indian Murakami reader, this is more than fusion food, it’s narrative fusion. A dish that contains exile, resistance, romance, and the blurred lines between fact and fiction.

You leave Nakamuraya not just full, but quietly altered.

Then there's Shinjuku, of course. Flashing lights, towering buildings, the faint scent of something frying two alleys away. Here, Murakami once ran a jazz bar called Peter Cat, long gone now, but immortal in South of the Border, West of the Sun. If you squint hard enough at night, you’ll feel it- the saxophone solo, the sting of loneliness even among crowds, the weird comfort of being invisible. There’s a hole in the wall joint called Dug nearby, dimly lit and full of vinyl, where you can sit with a Vodka Tonic and watch Tokyo breathe. If Murakami's characters are always slightly out of step with reality, then Shinjuku at 1 a.m. is the perfect ballroom.

As an Indian reader, there’s an odd familiarity to Murakami’s dislocation. Our cities are also layered. Delhi folds into Shahjahanabad, Mumbai has ghosts in its mill compounds, Kolkata remembers too much. But Murakami’s Tokyo isn’t about history. It’s about emotionally specific architecture. A stairwell where you fall in love. A kitchen that always smells like miso. A well that doesn’t exist anymore. These aren’t places. They’re portals. And when you step into them, your own past Hyderabad, Pune, Bengaluru, wherever comes along for the ride.

But perhaps the most Murakami-esque moment comes at Komazawa Olympic Park, not a site in any of his books, but a place he reportedly runs in often. I laced up my shoes and jogged alongside a few locals. No headphones. Just breath and wind and distant traffic. I thought of What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, his memoir, and felt for a fleeting second that I understood the man. That I understood myself.

Of course, I didn’t. You never fully understand Murakami. Or Tokyo. Or yourself. You just follow the trail. bookstores, bars, bridges and hope that something clicks.

In the end, walking through Murakami’s Tokyo isn’t just literary tourism. It’s emotional archaeology. You dig, you uncover, and sometimes, you mistake someone else’s memory for your own.

And maybe that’s the most Murakami thing of all.

Comments